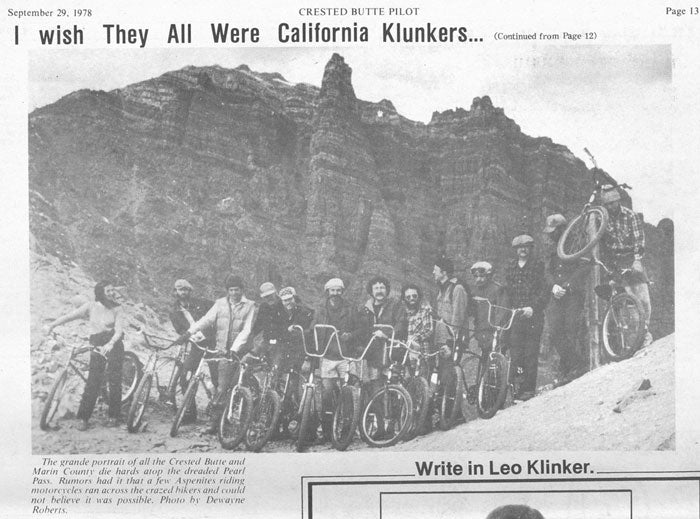

This interview was originally uploaded two whole years ago, but seeing as we're currently busy putting Pica~Post 9 together, we thought we'd dredge this up from the depths of time to give you something to read. Regular blog nonsense should resume shortly...

In the early ‘70s there was no such thing as mountain biking. A few people had tried putting knobbly tires on bikes and heading off-piste (most notably a man named John Finley Scott and his ‘woodsie bike’ in the early fifties) but no one had taken any notice. That is until a rag-tag gang of cyclists took to the hills of Marin County, California, armed with nothing more than pre-WW2 Schwinn cruisers. Although their explorations took them all over, the track that became famous was a particularly steep downhill fire-road called Repack (due to the fact that after just one run down it your forty year old coaster brake would need to be repacked with grease).

One of the main characters at Repack was Charlie Kelly, who as well as riding foot-out and flat-out down the track, organised and promoted the first downhill mountain bike races. He later went on to start the first mountain bike company with his room-mate Gary Fisher (the aptly titled MountainBikes) and was the man responsible for the Fat Tyre Flyer, which until 1986 was the only magazine devoted to off-road cycling escapades. Thanks to the wonders of the internet we managed to wangle an interview with him, and what follows could only be described as a bona-fide slab of real-deal rawness.

Photographs taken from Charlie’s website, header photo by Larry Cragg.

First things first, how’s it going?

I have nothing to complain about. I still enjoy life and still ride bikes at age 67.

Can you explain what exactly Repack was, and how it all began?

Repack is a steep hill near Fairfax where most of our activities too place. When we decided to have a contest of downhill it was the perfect choice. Very steep and nearly 2 miles long, it was a severe test of bike and rider. A few of us went out there and held a race, thinking that we would do it once and settle all the bets forever. It didn’t work out that way. Everyone wants a shot at the title, so we held a lot more races.

Around the same time you were working as a roadie for the Sons of Champlin in San Francisco, what led you to racing old bikes down hills?

I was a cyclist at that time, a rarity in the circles I travelled in. I had been president of my bike club, Velo-Club Tamalpais, and Gary Fisher and I shared a house. We had some old bikes that we used as our “town bikes” instead of riding our Italian race bikes. There are a lot of dirt roads and trails near where we live, and eventually we took the bikes out on them. It was so much fun we took it up as a regular part of our activities. Some of the other members of the bike club had similar bikes, and so there were already a couple of dozen riders when we held our first race.

Alan Bonds, Benny Heinricks, Ross Parkerson, Jim Stern and Charlie Kelly striking a pose with their Schwinn Excelsiors. Note the custom Excelsior t-shirts printed by Alan Bonds

How many people turned up at the first race?

The record of that race is lost, although I have all the others. It was six or seven people.

How did you go about promoting the races?

It wasn’t difficult. As soon as some guys from a nearby town heard that we had held a race, they wanted to take part also. So we held another four days after the first one. I had a list of telephone numbers that I would call before a race. Eventually I had an artist make posters, but by then we had already been racing for a couple of years. The purpose of the poster was to create documentary evidence of who was doing this and when. I could see that it was getting pretty popular, so I wanted to make sure I got the credit for it. And I did.

Two flyers promoting the ‘Repack Downhill Ballooner’

How did find all those old Schwinns? Did you have to modify them or did you just ride them as you find them?

At first it was easy, because they were considered junk. The problem was that those old frames don’t last very long when they are ridden the way we used them. Every six months or so I would need another. They became much harder to find, and the price was climbing rapidly.

It wasn’t long before you and your friends were designing your own bikes, what improvements did you make?

The most basic improvement was to make it out of chrome-moly steel. The old bikes were made of cheap steel that was heavy and not nearly as strong as modern bike tubing. Cantilever brakes were not as effective in wet weather as the old drums, but they were much lighter. Most of the other components were the same as we used on converted clunkers.

Charlie’s custom-made ‘Breezer’ built by Joe Breeze in 1978. Photo by Anne Ryarson

Can you give us an idea of what an average run down Repack was like?

If you’re not terrified, you’re not going to win. You have to ride right up to the edge of control and not make any mistakes that cost you time. The course is not technically challenging compared to a modern course made for long-travel bikes, but to date no one has shattered the old records set on clunker bikes. I believe that the reason we were so fast on the low-tech equipment is that we had a lot of races and plenty of practice on the course.

I remember reading stories about people skidding under fire-road gates at around 40mph, is there any truth in this?

40 mph on a road bike feels pretty fast. The average speed for the record run is around 27 mph. Obviously the top speed is faster than the average speed, but 40 mph seems a little high.

Alan Bonds with a foot-out, denim-heavy slice of high-action

Joe Breeze, Tom Ritchey, Gary Fisher… a fair few fast characters raced at Repack. Now the dust has settled a bit, who was actually the fastest?

Gary holds the record, but Joe won nearly half the races. Otis Guy has the third fastest time by only a couple of seconds, and on the run where he set it, a dog ran in front of him and brought him almost to a complete stop. If not for that, I believe he would hold the record.

Did things ever get heated on the mountain or was it all just a bit of fun?

It was always fun, but there were five or six riders who were the top guys, and the only real competition was among them. Since we started the fastest riders last, when it got down to just those guys and me, the starter at the top of the hill, things got very very quiet. Each guy would be by himself, getting his “game face” on.

When you weren’t racing at Repack, where else were you riding around this time?

I was always a road rider, although my racing career was brief and unspectacular. Most of the clunker rides were not competitive, but just a group headed out on trails.

If all the old pictures are anything to go by, plaid shirts, old jeans and boots seemed to be the uniform of choice, why was this?

It was the way most of us dressed anyway. I haven’t owned a necktie or a suit in a long time. If I got on the road bike, I changed into a jersey and shorts, but the whole idea of the clunker was that you just got on it.

You started the first mountain bike magazine, The Fat Tyre Flyer, in 1980. What led you to start a magazine?

It was an accident. We thought about forming a mountain bike club, so a few of us held a meeting. At the meeting my girlfriend (Denise Caramagno) and I volunteered to do the club newsletter. The club never had another meeting, but once we published the cheaply printed newsletter, people begged us to keep publishing it. So we did. Eventually I actually learned how to publish a magazine.

In an article you wrote in 1979 you said, “The sport that is going on here may never catch on with the American public.” Were you surprised when it did?

I’m still surprised. How could anyone have predicted that a goofy hobby that most people laughed at would take over the world?

Do you still ride mountain bikes now?

Sure do, and they are much nicer than the ones I started on. Gary Fisher has made sure that I ride quality equipment, currently a pair of Gary Fisher 29ers.

Nowadays you work as a piano mover. Can you divulge any tricks of the trade?

I figured most of it out by doing it. There are certain qualities that are vital, in addition to being reasonably strong. Size matters. A 200 pound guy can do more than a very strong 150 pound guy. (Unfortunately, size also matters in bike racing, but in the other direction, which explains my undistinguished bike racing career.)

My aptitude for “spatial relations” always tested very high. I can visualize three-dimensional concepts, but I’m pretty sure all piano movers are like that. Being smart is as important as being strong, and you need both qualities. No two situations are identical, but with years of experience you can usually find a comparison to something you did before, which shortens the process of deciding how to approach a job.

Anything else you’d like to say?

Buy my book. It should be out some time in the next six to eight months, entitled “Fat Tire Flyer.” Maybe we’ll do an English version and spell it properly, “Fat Tyre Flyer.”